However regrettable it is to admit, one of my earliest aesthetic influences was a video game called World of Warcraft. In vivid recollection I recall the scenery of one of the zones in the game, called “Westfall,” and the various impressions it made. The scenery resembled the American Midwest with some interesting additives: large expanses of rolling hills, wheatfields with mechanized “harvester-golems,” bundles of okra, scarecrows, abandoned houses and not-so-abandoned farmhouses, bands of furry humanoids and rogue syndicates (which, if public gamer-knowledge is to be acknowledged, was based on a real-life historical group from Austin, Texas), and more. The scenery reminded me of an iconic, hybrid cross between Kansas and Oklahoma. It was a beautiful aesthetic depiction of an environment that would have been difficult for a young boy to encounter without the considerably indulgent aid of a video game.

Well now, the other day, I decided to craft a scarecrow to place in the garden on the (partial) homestead we live on. It was an enjoyable activity, and one my elder-daughter found amusing: I crossed two posts and hammered the crossed-section with nails, hung a faded flannel (which I supplied for the effort out of a desire to become detached from a shirt I had come to love) of green, maroon, and beige across the horizontal post, and then I suspended an old pair of dark-blue jeans below the flannel using some shop cord. Then, I sealed off the ends of the clothing with the same shop cord and began stuffing straw into the openings. I snagged some bundles of plastic grocery bags, stuffed the torso with them, and filled out the remaining areas with straw. I then fitted two large scraps of burlap over a basketball, removed the basketball, and stuffed the impression with straw. Wiggling the small opening of the now stuffed head down on the top post, I secured the head to with more cord and set the scarecrow structure up to the base of a pecan tree to get an initial look. Having secured all the ends, making a deep enough hole with a postal digger, and filling the hole in with the excavated dirt, I finally erected the scarecrow in his home dirt. I scribbled some eyes and a mouth on his burlap head with a black marker and flipped-up an old green ballcap on his head. I stepped back to observe the final product. My wife walked up. “What’s his name?” she asked. “Douglas,” I replied. “Or Doug, for short.”

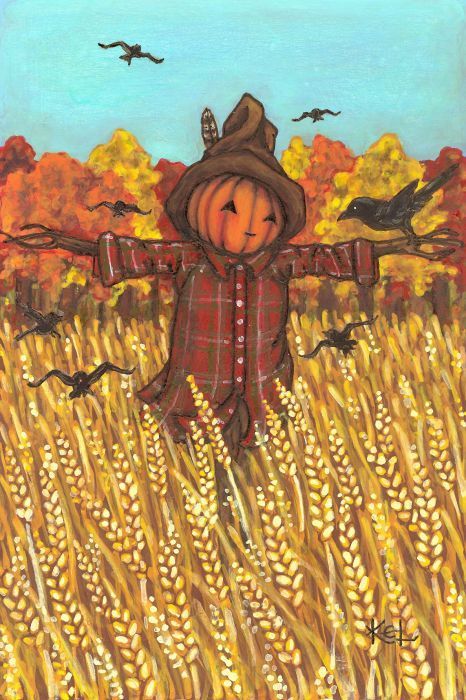

As I observed this unexpectedly skilled creation of mine, I realized I had made something that was, for me, a representation of aesthetic imagination I had first been impressed with in my boyhood. In late summer, standing there at the forefront of a North Texas garden, I was in a “Westfall” of my own. There, in the Northern Blackland Prairie of Texas, I was near the border of an imagined new land, a picturesque hybrid of Oklahoma and Kansas. The Texas hay became as golden wheat; the scorched cornstalks became like signs of Dorothy’s light depression; and the yellow coloration of the scene, mixed with the green from the pecan trees, sufficed to provide my near-autumnal scarecrow with a spiritual coloration worthy of lifting my senses to a treasure of my own. I was in a mild state of awe, and I took a sharp mental note about it: philosophy and art are more than neutral parties, for they conspire to bring out the most delicate, sincere, and truthful sensations of our earliest recollections.

And I’m in good company for thinking so.

Perhaps no poem better encapsulates the poet’s mood on the subject than “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood,” written by the great Romantic poet, William Wordsworth. If we may attribute to Wordsworth’s poem the following philosophical judgment (which I believe we can as it’s surely evident enough in the poem): the truths of the “exterior semblances” of the soul’s immensity rests within the philosophic mind as it apprehends and considers the external thing in question because it is the philosophic mind, “haunted forever by the eternal mind” yet retaining a heritage, an “Eye among the blind,” that “read’st the eternal deep.” In the heritage of the eternal mind, the philosopher is both mighty prophet and blessed seer, for he reads the eternal aspects off of exterior things, and recaptures the immensities discerned within himself from his earliest impressions. There was really only one question to consider as I gazed upon the strawman hanging upon a cross: What is a scarecrow?

To put it plainly, the scarecrow is a double of sorts. It represents a doppleganger only mythically. (Think of the horror movie, Jeepers Creepers, where the scarecrow is featured as an abominable doppleganger). But as a true double, the scarecrow serves a primary two-fold purpose. The scarecrow is effigy and ward. As an agricultural effigy, the scarecrow is an icon of a culture persevering under weight (gravitas) of its own construction, and could be scorched by the intensity of its situation. In this regard, the scarecrow is weighed by philosophical and religious significance. A scarecrow erected upon a short beam without its arms having a robust volume of hay will soon begin to resemble a human form bent at the elbows because the end of the wooden beam will jut out where the elbows would normally be while the forearm area of the scarecrow’s attire hangs loose. Religiously and legally speaking, the scarecrow symbolizes a victim forced to hang under the weight of another’s stratagems and machinations.

At another, lower plane of understanding, is the effigy as a symbol of decline or fallenness due to the weight of the socio-cultural predicament it stands for. This socio-cultural predicament is that of the farmer. Edwin V. O’Hara, one of the leading figures in reviving rural life in America, once noted that the original problem concerning the upkeep of rural culture was the problem of “maintaining on the land a sufficient population effective and prosperous in production, and happy and content by reason of a highly developed social and cultural status” (“The Rural Problem and Its Bearing,” 16). The scarecrow, then, is agricultural effigy in the sense that it symbolizes what happens when the agriculturalist (the farmer) is denied the robust volume of a robust culture–without such a highly developed social and cultural status, he hangs; without it, he is “left out to dry” like straw in the summer heat. Treated like a scarecrow without a brain, the farmer is castigated, admonished, and held in contempt–often by those who, despite having a brain, are devoid of heart. But as we shall soon see, the poetics of the farmer never imagine the farmer as heartless.

As a ward, the scarecrow is functional, practical, artifactual, purposive. The farmer would pay little heed to the notion of scarecrow as effigy unless it becomes cultural dire. The scarecrow as effigy is for the theologian, the philosopher, the poet, the artisan. It is abstract, speculative, contemplative. And we would fail to understand the farmer as farmer if we regarded him as one who must understand the scarecrow in such a way. But the farmer may still perceive the scarecrow as an object in a landscape that he loves. In this way, the scarecrow, even as primarily a practical ward to protect his crops, is for the farmer something definitively artistic–that is, the scarecrow is fashioned with materials from his farm, is established for his practical purposes, and now adorns his farm’s scenery. Seeing the strawman lifted on high, the farmer–who, as James Rebanks remarks in his memoir, The Shepherd’s Life, using Wordsworth, is neither romantic nor sentimental about his abode and land at all–nods his head approvingly. The farmer nods his head at his practical ward, a symbol of “matter-of-fact” utility which betokens the somber heritage of his profession.

Nevertheless, the scarecrow as ward is still an almost animated being of practical utility. The farmer acknowledges, on one hand, that the scarecrow is a wholly lifeless being, an amalgamation of parts, while also acknowledging, on the other hand, that the scarecrow serves a vital purpose to protect “his” crops from scavengers. The scarecrow of course cannot protect his crops from all scavengers, and so the scarecrow’s practical purpose is limited. But for whatever reason, it seems the scarecrow as ward cannot remain at this functional-practical level, even for the farmer. Even the farmer must look for other constructive significances and meanings, even if only in the sense that the farmer is belongs to a community, a family. And I think it is here, at a constructive significance manifesting as some cultural staple of rural life, that the farmer contents himself to rest without any need to inquire any further. But what exactly is the meaning of the scarecrow as a “cultural staple”?

Perhaps we may consider the reason why a farmer would rest with the scarecrow as “cultural staple” by looking into another poem. In W.B. Yeats’ poem, “The Happy Townland,” he describes the feeling of festivity in a rural townland intermingled with the rather wearisome feeling of toil in the farmer. In the overflowing mirth of brown and red beer, in the setting of old men bagpiping in golden-silver woods and fine ladies dancing with ice-like blue eyes, with the hearts of townsfolk high and the hearts of farmers sapped and drunken, with the sweet laughter of little creatures alongside the creaturely feelings of banality–: there the meaning of the scarecrow as a cultural staple meets the more robust meaning of the scarecrow as effigy. This merged being is a culturological item of eternal depth and practical concern, like the first chill of autumn meeting a twofold premonition of reason in both the sounds of crows cawing and the smells of a pumpkin-spiced hearth. In a merger of eternal depth and practical concern, in the culturological poetics of sentiment and feeling and natural cycles, there the scarecrow hangs amid the uncanny, the bizarre, and the quiddities of prophetic rhythm. The truth of this merged being is the scarecrow that hangs on God calling souls deeper into God and creation.

The final few lines from Yeats’ poem are puzzling. However unusual they may seem at first to argue for the truth of the scarecrow, I believe they evince a merged cultural item of effigy and ward, theory and practice, eternal significance and practical convention. That is to suggest, the lines represent a lesser world being drawn up to consider the making of a higher world: one in which the human mind is at true liberty to fashion for itself icons of imperishable worth in the refulgence of contemplation.

Michael will unhook his trumpet

From a bough overhead,

And blow a little noise

When the supper has been spread.

Gabriel will come from the water

With a fish-tail, and talk

Of wonders that have happened

On wet roads where men walk.

And lift up an old horn

Of hammered silver, and drink

Till he has fallen asleep

Upon the starry brink.

Leave a charitable reply!